A Look at Kenya's Educational Landscape

Every child in Kenya has the right to an education. But the path to the classroom is not the same for everyone. Where you are born, the infrastructure around you, and your family's circumstances can create steep barriers or smooth the way forward.

In this project, I worked with data from the Kenyan National Household Survey to understand these barriers. I wanted to move beyond broad national statistics and uncover the specific, local factors that shape a child's educational journey.

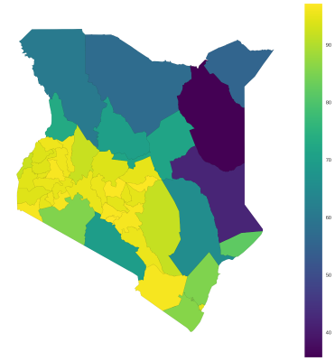

The story the map tells

The first thing I did was plot the data on a map.

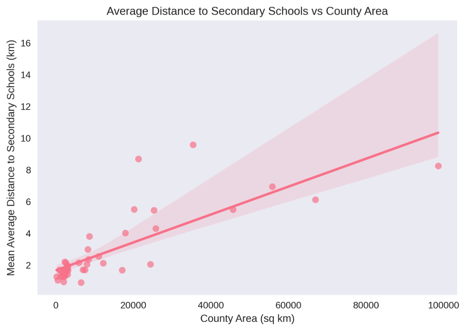

A county-level map of school attendance reveals a geographic disparity, with northern regions, which are also the more sparsely populated, showing lower rates. An analysis of average distance to schools reveals a plausible cause for this pattern: these same regions with lower attendance also have the longest travel distances to schools, particularly for secondary education.

This relationship is particularly pronounced for secondary schools, where larger counties generally have schools located farther from households.

However, this was not the same for primary schools, where no strong direct relationship between distance and county area was found. This suggests a successful policy of ensuring primary schools are relatively accessible even in remote regions, which is reflected in the data showing most individuals surveyed have at least a primary education.

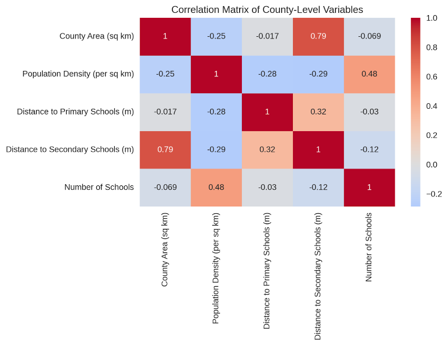

Population density shows a moderate positive correlation with the number of schools. Where more people live closer together, there are more schools. It also has a negative correlation with distance to schools, meaning denser areas have shorter travel distances.

The story within the household

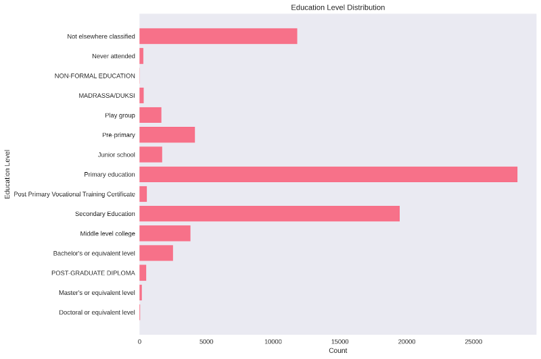

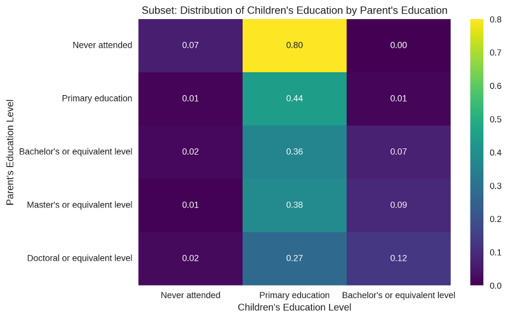

Beyond geography, the dynamics of one’s household shape their educational destiny. You might assume that parents who never went to school would see their children follow the same path, but the data reveals something contrary. These parents are ensuring that their children get at least some form of education, as a majority of their children have attained at least primary and secondary education. However, they struggle to advance to higher education. The barrier isn't getting them to school but getting them through it. In contrast, children of university-educated parents are far more likely to reach similar academic heights.

Looking at family members' education levels in a household, the older generations are far more likely to have never gone to school or to have only basic education. In contrast, their grandkids are filling primary and secondary classrooms. This contrast indicates that today's youth have significantly better access to learning opportunities than their predecessors ever did.

There is a rural-urban divide in education access. While it's true that a larger number of surveyed individuals lived in rural areas (61.4%), the important finding lies in the proportion. In rural areas, 17.6% of the population reported never attending school, a rate higher than the 10.9% from urban centres. It was also evident that there was a link between electricity and a person's education. Households with power had higher school attendance rates than those without. Think about what electricity enables: light to study after sunset, charged gadgets, and potentially an internet connection. It turns a home into a place where learning can happen. Without it, a child's potential is literally left in the dark.

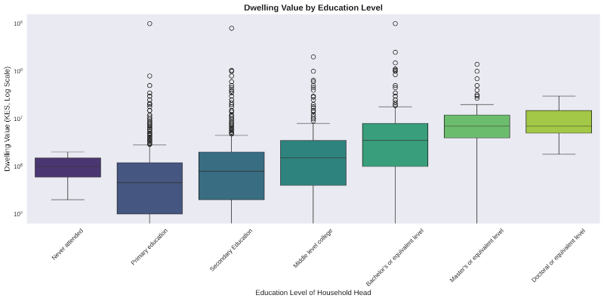

So, what's the payoff for all this schooling? Since employment data was confidential, I looked at the house value. As the education level of the household head rises, so does the median value of their home. The more educated the head of the household, the higher the rent they can afford and the more valuable their owned home. This is strong indication that education translates into a better quality of life.

Conclusions

Individually, each of these findings tells a part of the story. But while data can map the challenges, it’s important to remember what it cannot measure: the resilience of a student walking miles to school, the determination of a parent sacrificing for their child’s future, and the power of a young mind eager to learn. Ultimately, the most important factor in a child’s education is not found in a dataset - it is the human spirit, and that is a resource Kenya has in abundance.